25 Personal interventions

Consumers can and do use their own behavioural interventions to overcome their own limitations.

25.1 Commitment and self-control

One of the primary ways consumers can do this is through committing themselves to a future course of action. If they have a degree of sophistication and know that they may fall victim to present bias in the future, they can act now to remove that possibility.

A simple way people can do this is by placing their savings into a less liquid investment, such as a term deposit. In one experiment, Beshears et al. (2020) found that when people can invest in two accounts, one liquid and the other with liquidity constraints such as withdrawal penalties, the experimental participants put nearly half of their money in the illiquid account even though it paid the same interest rate. This contrasts with the standard economic prediction that all money should go to the liquid account, which enables all actions plus more than can be done from the illiquid account. Even when the interest rate on the illiquid account was lower, it still attracted around a quarter of the money.

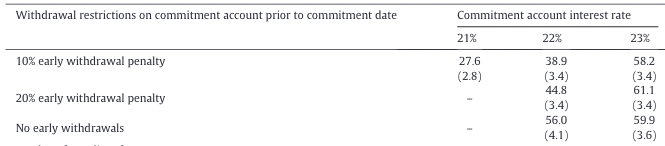

This extract from Table 3 in the paper shows the proportion of funds allocated to each type of “commitment account” when experimental participants were given a choice between an account with no liquidity constraints paying 22% interest and the commitment account.

You can see that where the interest rates between the liquid and illiquid accounts were equal, the accounts with harsher constraints attracted more money. The account with a higher withdrawal penalty (20% compared to 10%) attracted more money, and the account that barred withdrawals attracted even more.

This result suggests a demand among sophisticated, present-based agents for products that will enable them to control their future behaviours.

25.2 Mental accounts

Mental accounts can often act as a form of commitment despite the absence of any physical barriers.

One example of mental accounts that we have already come across in Section 13.1.3 is the co-holding of savings and debt to create constraints against even worse outcomes. People often hold both high-cost credit card debt and savings that provide low rates of return (Gathergood and Weber (2014)).

Co-holding the two can be a self-control strategy. A failure to divert the savings to pay off the credit card decreases the amount of unused credit capacity, which may reduce future spending.

Another example of the use of mental accounts working as a control was an intervention designed to help micro-entrepreneurs in the Dominican Republic make financial decisions (Drexler et al. (2014)). They were placed in one of two programs. The first was standard accounting training. The second was a rule-of-thumb training that taught basic financial heuristics. The major heuristic was for them to physically store their their household and business money in separate drawers.

The rule-of-thumb training improved their financial practices and revenues. Among those with lower skills or poorer initial practices, the rule of thumb training had better results than the accounting training. (While being seen as a self control mechanism that can be implemented by someone, this could also be seen as a tick for a non-traditional financial literacy intervention.)